Crucible steel was still in demand well into the twentieth century, despite competition from the spectacularly successful (and much cheaper) large-scale production processes introduced by Bessemer and Siemens.

Enduring qualities

This account from 1905 describes a processes essentially unchanged since its invention over 150 years earlier, and still reliant on Swedish bar iron that had been ‘converted’ to blister steel using the lengthy and inconvenient cementation process:

For the great majority of purposes when the highest class material is required there can be little doubt that the best method is to use most carefully selected blister steel taking care to exclude all bars which are harder or softer than the temper required and all flushed or aired bars and to melt it in the crucible.

The metallurgy of steel, By Frank William Harbord, John William Hall. 1905

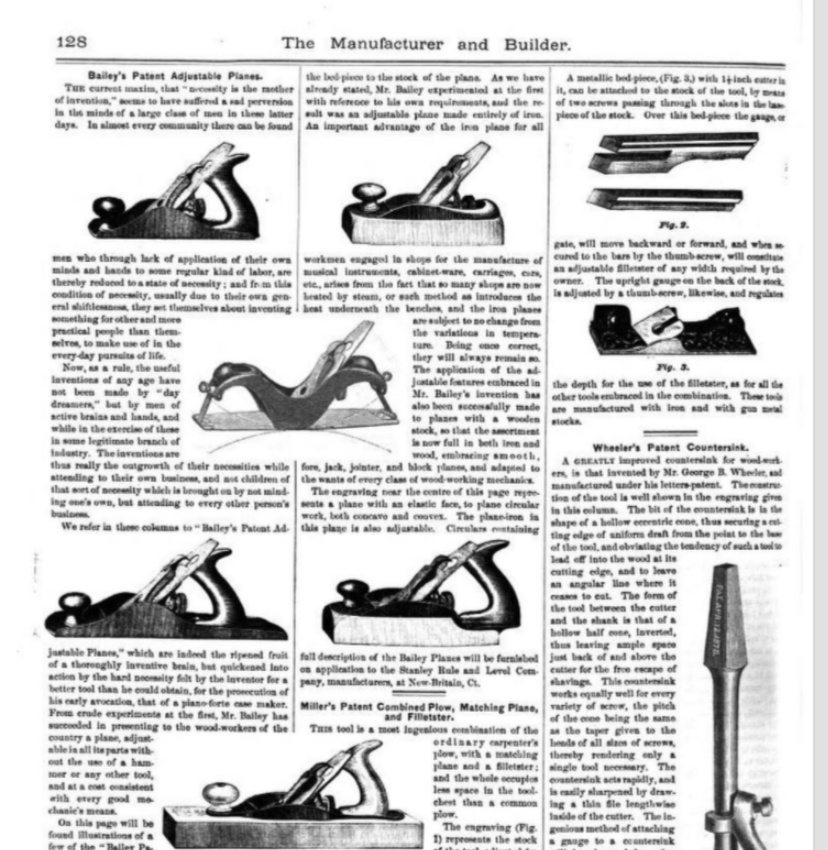

Edge tool makers in particular continued to insist there was no steel better suited to their purpose and paid a high premium accordingly. Although tradition and conservatism within their trade may have contributed to the surprising longevity of the crucible steel production process, another important factor was that it lent itself to the making alloy steels where the small crucibles used were convenient for preparing the precise special mixtures needed.

Steel alloys allowed the development of the faster cutting machine tools demanded by industry and this alone was reason enough for many steel makers to sustain their crucible furnaces alongside their rapid adoption of newer technologies

The first commercially important alloy steel – known as Mushet’s Special Steel – was invented in 1868 by Robert Mushet when he discovered that the introduction of a certain proportion of tungsten and manganese to mild steel resulted in metal that hardened when allowed to cool in air after it was forged. By comparison, traditional carbon steels had to be heated to a very high temperature, quenched and then tempered to an appropriate hardness before they could be put to use.

Mushet’s alloy found many important uses in machine tools and also paved the way for the development of the improved alloy mixes used in a range of steels known today as ‘High Speed Steels’.

Electric Furnaces

The crucible process was the preferred method for creating these alloys until the end of the first World War[1] , but during the 20 to 30 years following it was to be eclipsed by the introduction of electric furnaces. Here is an electric furnace installed by March Bros, Sheffield – the picture is probably from the 1940s:

These furnaces – basically containers wrapped in a copper coil which, when suppled with a current, created temperatures high enough to melt the contents -were very convenient since they did not require a regular supply of clay crucibles and could be turned on and off as needed without lengthy and dirty pre-heating.

The technology was soon adapted for alloy making and by the end of the 1920s many steel makers were moving their alloy production to the new furnaces and the old crucible furnaces were retired.

The last crucible furnace

After a brief resurgence of interest during WWII when the ceaseless demand for steel necessitated the reopening of some of the mothballed crucible furnaces, use of the old technology was in steep decline, and by the 1950s was all but gone:

“To-day, the number of such furnaces still working in Sheffield can be counted on the fingers of one hand”

Three Centuries of Sheffield Steel, The Story of the Marsh Bros, Ltd, Sidney Pollard, 1954

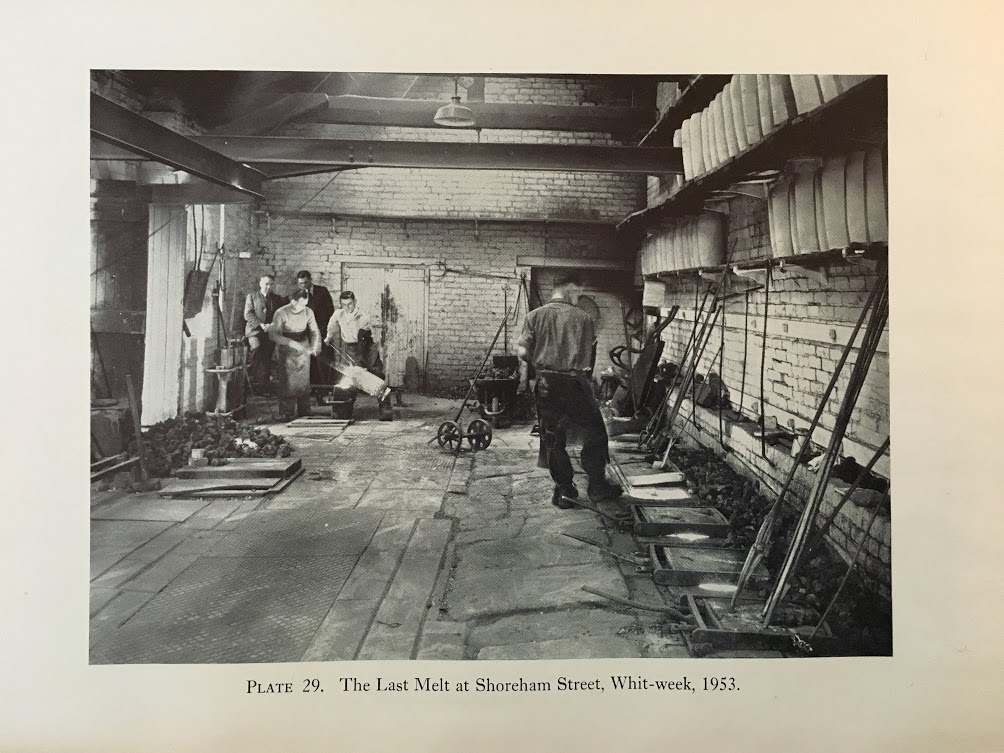

Marsh Bros closed their own crucible furnace in 1953:

Stanley & Record, a footnote

Modern steel production processes include facilities to conduct chemical analysis as the metal is melted, computer aided temperature control and automatic weighing, mixing and pouring. While it is surely true that these advances eliminated some of the potential for human error inherent in the crucible method, it does not necessarily follow that high quality steel could not also be produced reliably and consistently using the old techniques.

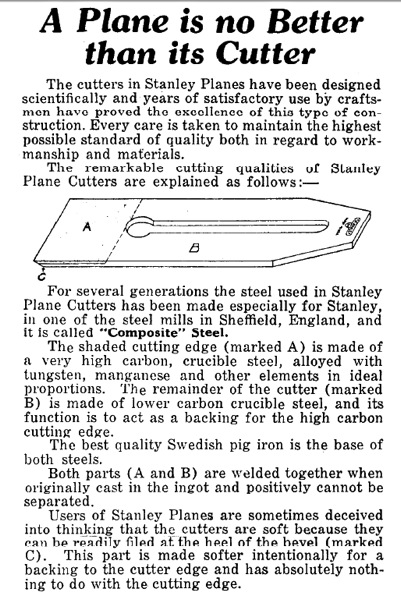

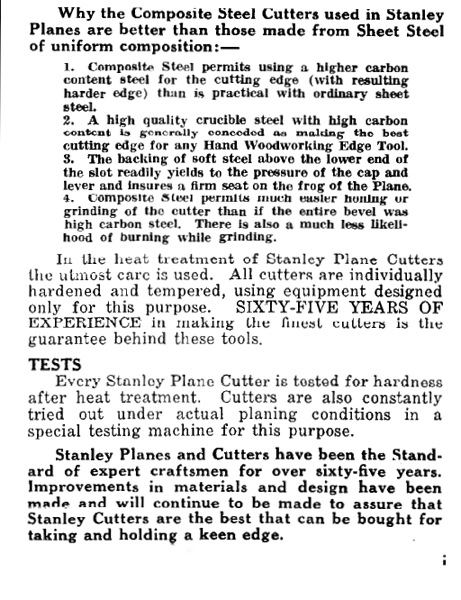

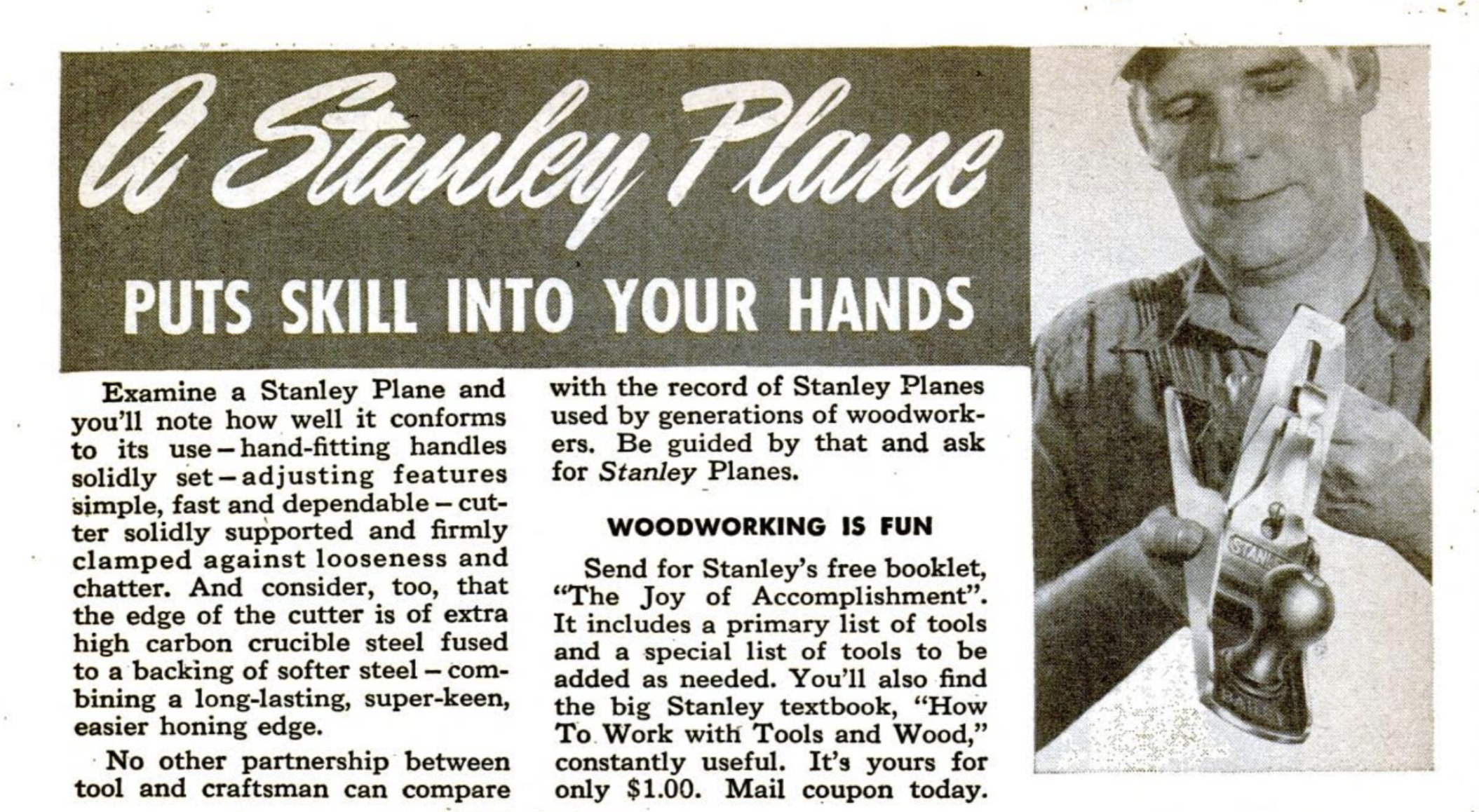

It is testament to the skill and experience of the Sheffield steel makers that major tool manufacturers like Stanley and Record continued to use crucible steel until the very last moment, only stopping when the manufacturing capabilities finally disappeared. Stanley were so confident of the quality they were getting that they mentioned it in their own sales literature:

For several generations the steel used in Stanley plane cutters has been especially made for Stanley in one of the steel mills in Sheffield, England…

The best quality Swedish pig iron is the base … [and] a high quality crucible steel with high carbon content is generally conceded as making the best cutting edge for any hand woodworking edge tool Stanley Advertisng flier

The flier is undated, but given the reference to "65 years of production" and the fact Stanley introduced their Bailey planes in the early 1870s we deduce it dates from the late 1930s

Here is a later mention (1946):

And then finally in 1959, we hear that crucible steel blades have been discontinued

The new Stanley cutter is made of Nickel Chrome Alloy Steel throughout (The old-fashioned composite steel has been discontinued)

Education, Volume 114, 1959

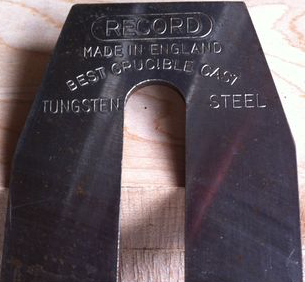

Record also used crucible steel, stamping the same on their irons until 1959:

Despite Stanley’s copywriters putting a brave face on the situation, it is probable that the move away from crucible steel was necessitated by the closure of manufacturing facilities in Sheffield rather than attempt to adopt a better alternative. Given how few crucible furnaces were left by the 1950s, it is conceivable that Record and Stanley shared the same supplier and were both forced to adopt a new source of steel at the same time.

And thus, after over 200 years of continuous production, the era of Sheffields world famous crucible steel drew to a close.

References

| 1⏎ | The Iron Age, August 25 1921 |