Although this article is about blades used in wooden planes there is an interesting parallel between the blade choices available to wooden plane users at the start of the 20th century and the choices facing metal plane users at the start of the 21st who must choose between thick vs thin irons.

Old wooden planes were generally equipped with thick irons, and as a rule, these were tapered from tip to the toe, so that the fat part is at the cutting end.

This is a convenient arrangement for a wooden plane since the blades are held in place by a wedge and the taper of the blade increases the wedging effect. This means you need to tap less hard on the wedge to hold the blade firmly in place – a good thing since if you clout the wedge too hard it can damage the body of the plane.

Parallel blades

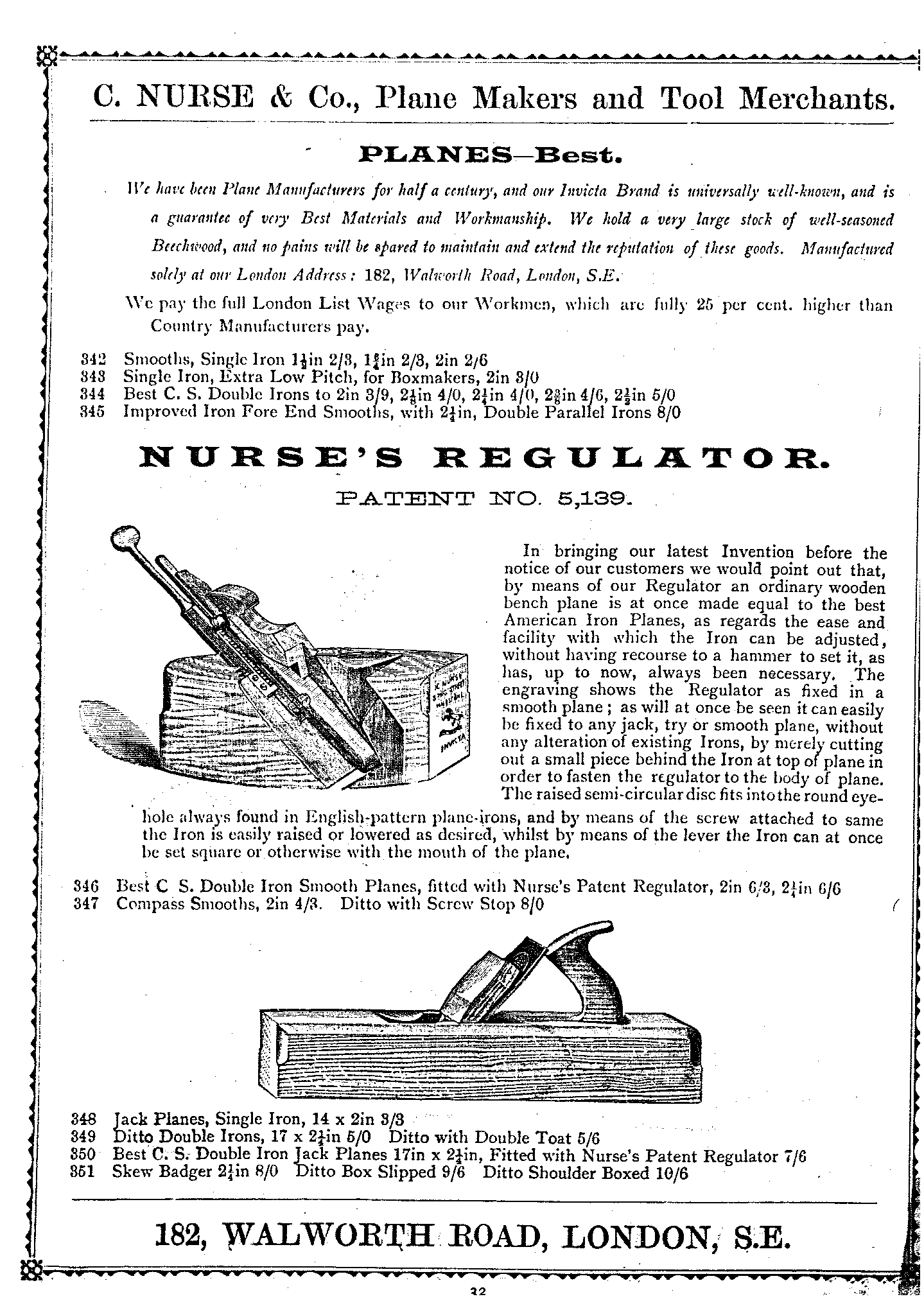

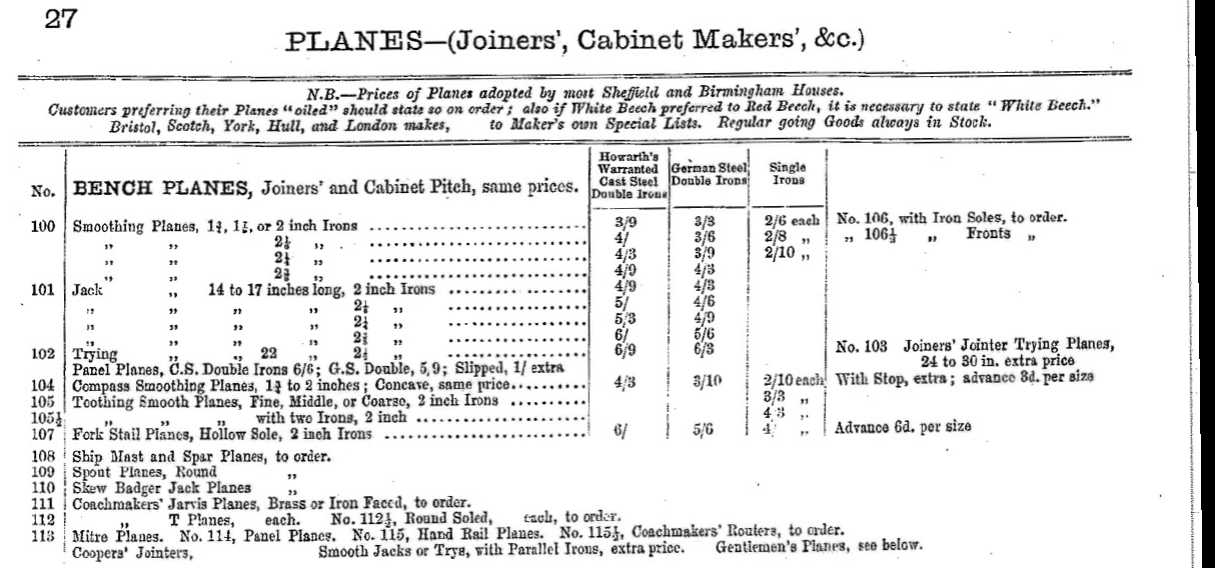

Parallel blades for use in wooden planes can be found advertised in several catalogues from the late 19th century.

The 1884 Howarth catalogue has a parallel iron as an option on all the bench planes, but the Nurse catalogue offers it for smoothers only. You can see similar options in the early 20C Marples catalogues too[1].

As you can see in the catalogues, by the end of the 19th century parallel irons were being offered as a more expensive alternative to the standard tapered offering.

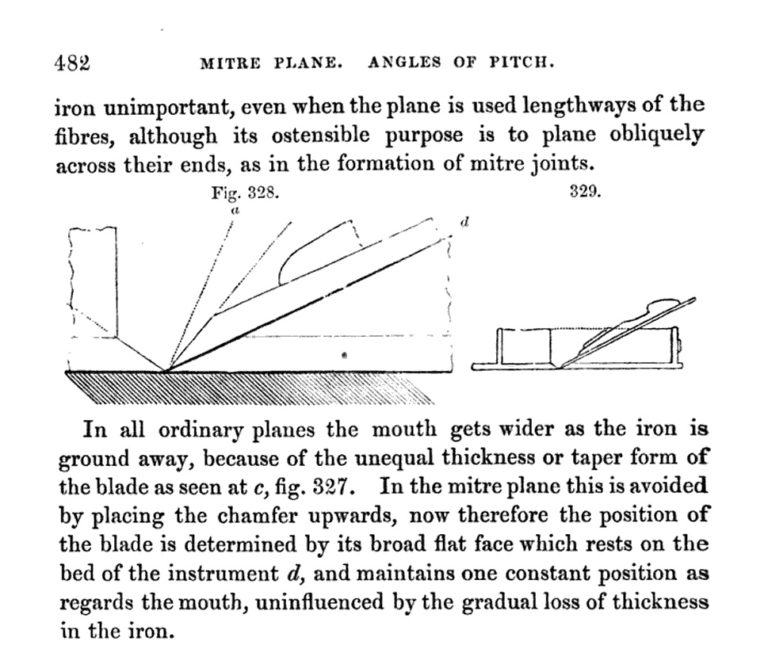

It is not clear exactly when parallel blades were first introduced for wooden planes, but this is a snippet from Turning and Mechanical Manipulation Volume II – published in 1846 by Charles Holtzapfell – suggests that at the time only “ordinary” (bench) planes only used tapered blades:

Infill planes

Parallel irons were certainly popular with users of the high-end metal bodied planes made by Spiers, Slater and Norris from the 1840s onwards

These expensive infill planes – so called because of the wooden components that fill the metal body – often use a lever cap that is screwed tight to hold the blade so that the additional wedging effect created by a tapered blades is of no advantage.

But why would makers try to sell the same parallel blades to wooden plane users, where the shape requires more wedge pressure to hold in place, and is thus a disadvantage in relatively fragile wooden planes? I suppose marketing may have been a factor, the parallel blades perhaps appearing more attractive by association with prestigious inflill planes, but another theory relates to a limitation of tapered blades.

Tapered blades and mouth gap

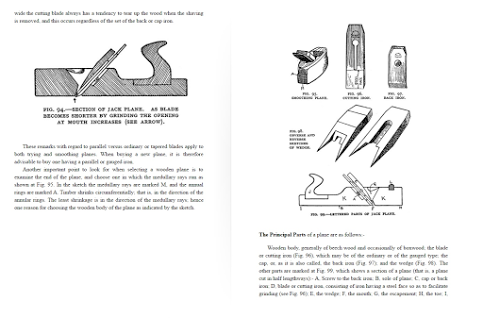

Like all blades, tapered blades get shorter as they are sharpened and – because metal is removed from the fat end – this means they get gradually get thinner too. A consequence of this is that when set up in the plane, the blade tip ends up being slightly further away from the leading edge of the mouth each time it is sharpened. The effect is to create a mouth gap that gradually widens over time. (Compare this to parallel blades where the mouth gap stays the same no matter how much they are sharpened).

Quite likely this fact would be of interest to people who like to keep a tight mouth on their planes to control tear-out[2].

This topic is discussed in Modern Practical Joinery, by George Ellis (1902):

Bench Planes.—The Jack Plane, f. 1, is the first plane used in preparing stuff, its purpose being to remove irregularities left by the saw and produce a fairly smooth surface. It is also used generally for reducing scantlings quickly. It consists of a beechwood stock 17 in. long by 2 3/4 by 3 in., with a 2 1/4-in. cutting iron and similar back iron. The cutter is better parallel or gauged, as once fitted, the wedge will then always sit properly, and the size of the mouth remain the same throughout. This applies to all planes whose cutters are fixed by wedges.

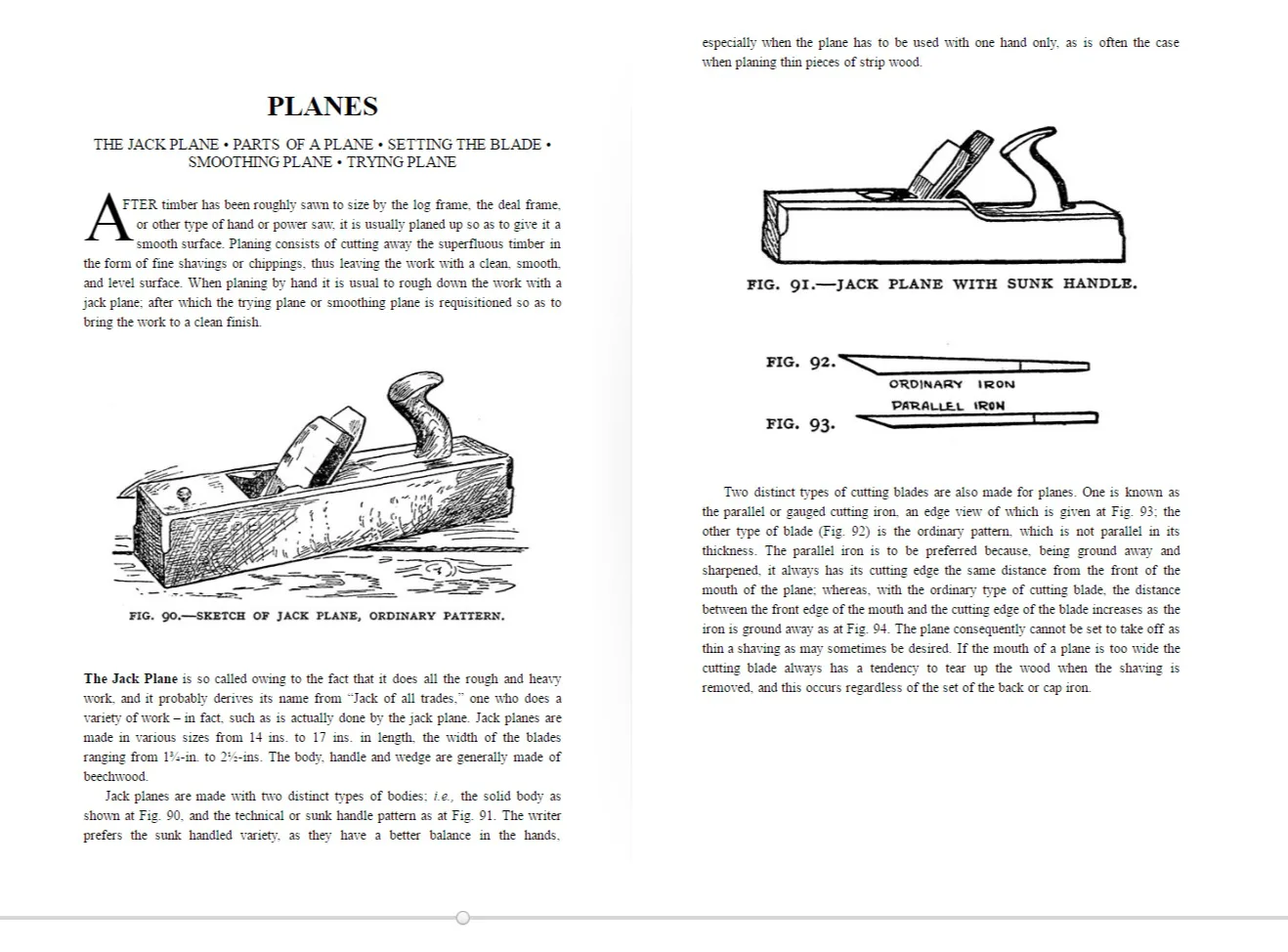

and in William Fairham’s book, Woodwork Tools and How to Use Them:

It is true that as tapered irons are used up they get thinner and thus the mouth opens, but is this a compelling reason to switch to parallel blades?

At this stage we should note that the soles of wooden planes need periodic flattening because of wear and tear and movement caused by changes in moisture levels. If you look closely at wooden bench planes you will see that leading edge of the opening in the plane in which the iron sits is angled forward to allow shavings to more easily escape, and this means that as the plane is trued up and material is removed from the sole, the mouth widens.

In the spirit of scientific research I bought a parallel blade to replace the worn out tapered iron in my wooden jointer.

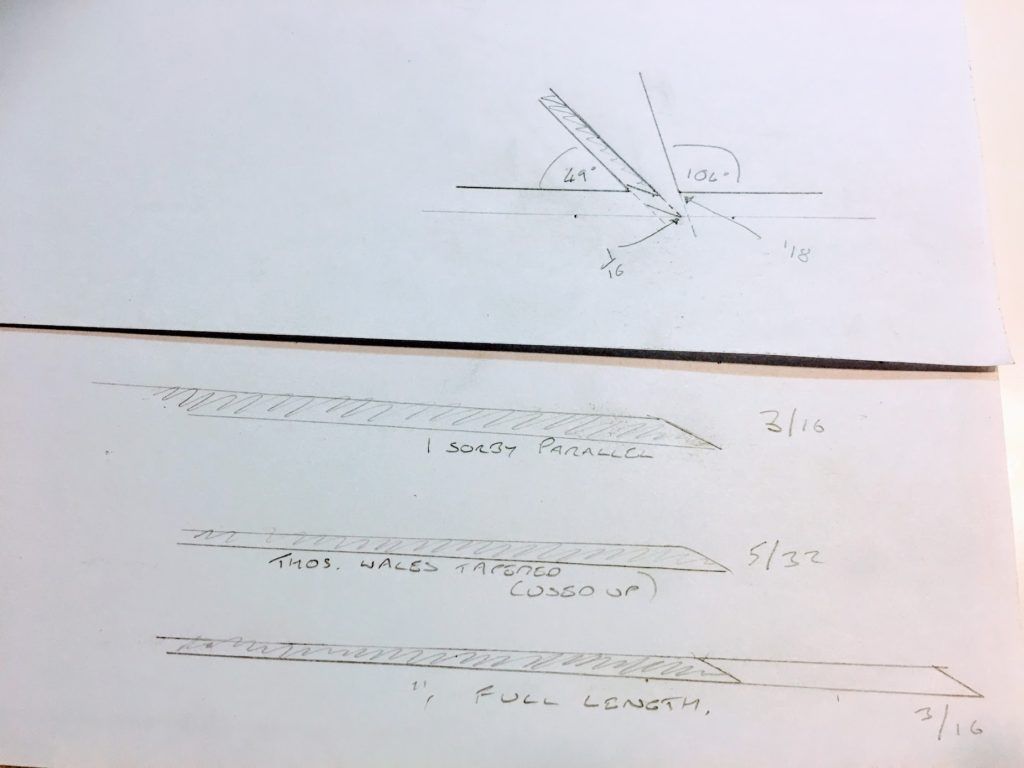

The used up blade on the right is from Thos Wales – the last date I can find for this maker is the Midland Tool works, Sheffield in Whites Directory of Sheffield & Rotherham – 1911.

The previous owner had created a small leather packer to fit under the blade in an attempt to close the mouth of the plane somewhat.

The plane itself was made by Thomas Turner, a maker that apparently traded up until 1912. Here is an example of their trademark (from another plane, the trademark on the jointer is a littler hard to make out)

Although not relevant to this little experiment, the replacement iron is made by I Sorby (coincidentally it came with a cap iron made by T. Turner).

Extrapolating from the worn out Thos Wales blades’ taper I calculated that this blade would have been 3/16” (4.7 mm) at its widest point when new, assuming there was around 2 1/2” inches of useable iron originally. In it’s reduced state the iron is 5/32” (3.9 mm) at its widest point. In other words, the effect of a lifetime of sharpening was to reduce the width of the tip by about 1/32” (0.8 mm), which will have had the effect of widening the gap between the tip of the blade and the leading edge of the mouth by the same amount.

How does this compare to the inevitable widening of the mouth that comes from the wearing and flattening of the sole? I worked out that, had my plane lost a 1/4” of an inch from the sole over the length of its life – as is plausible, since this would have meant it was originally 3 1/4” square, rather than the 3 1/4” x 3” that it is now – then the distance between the blade edge and the front of the mouth with a full length tapered blade would have been half what it is now. This means the mouth gap was originally 1/16” (1.6mm) and a century of flattening has increase the gap by a further 1/16".

Conclusion

So there you have it, on a not very scientific survey of one plane, over around 100 years the mouth opened up 3/32” (2.4 mm) – a fair old gap – and about a 1/3rd of this was caused by sharpening the tapered blade and the rest from flattening the sole.

Considering that plane mouths inevitably widen due to periodic flattening, and seemingly at a faster rate than could be offset by using a parallel blade, it is hard to disagree with Steve Voigt in this woodcentral discussion:

it seems like parallel irons were something that was offered at the twilight of the woodie era, based on some misguided notions about blade life and mouth opening. Interesting, but mostly a historical curiosity, I think woodcentral.com

References

| 1⏎ | these catalogues are available from Taths |

| 2⏎ | one of several options to reduce tear-out, c.f this previous post for an explanation |