Given the main purpose of bench planes is to smooth and flatten wood it is unsurprising that the sole of the plane should be flat, but views differ on exactly how flat it needs to make them work optimally.

Flatness standards

To understand why flatness is important we can consider the mechanics of the plane: if you imagine the sole of a plane that is significantly convex – in other words it has a “belly”- then you can also see how it would tend to rock from side-to-side or end-to-end as you pushed it across the work, meaning the blade would not make consistent contact with the wood and resulting in a unsatisfactory finish.

If it is concave – that is, it has a hollow – then the blade and mouth can be held above the surface of the wood and, in order to make a cut, you will have to extend the blade beyond the mouth than would be necessary otherwise. The result is that the blade is unsupported by the frog for a relatively long distance and, because the wood is not compressed by the leading edge of the mouth, tear-out is more likely.

So, hypothetically, having anything other than a completely flat sole is bad news. But what about in practice? Exactly how flat is necessary?

In true British fashion we have a rule telling us whether a plane sole is flat or not – the relevant British Standard is BS 3623:1981 Specification for Woodworkers’ Metal-Bodied Planes[1]:

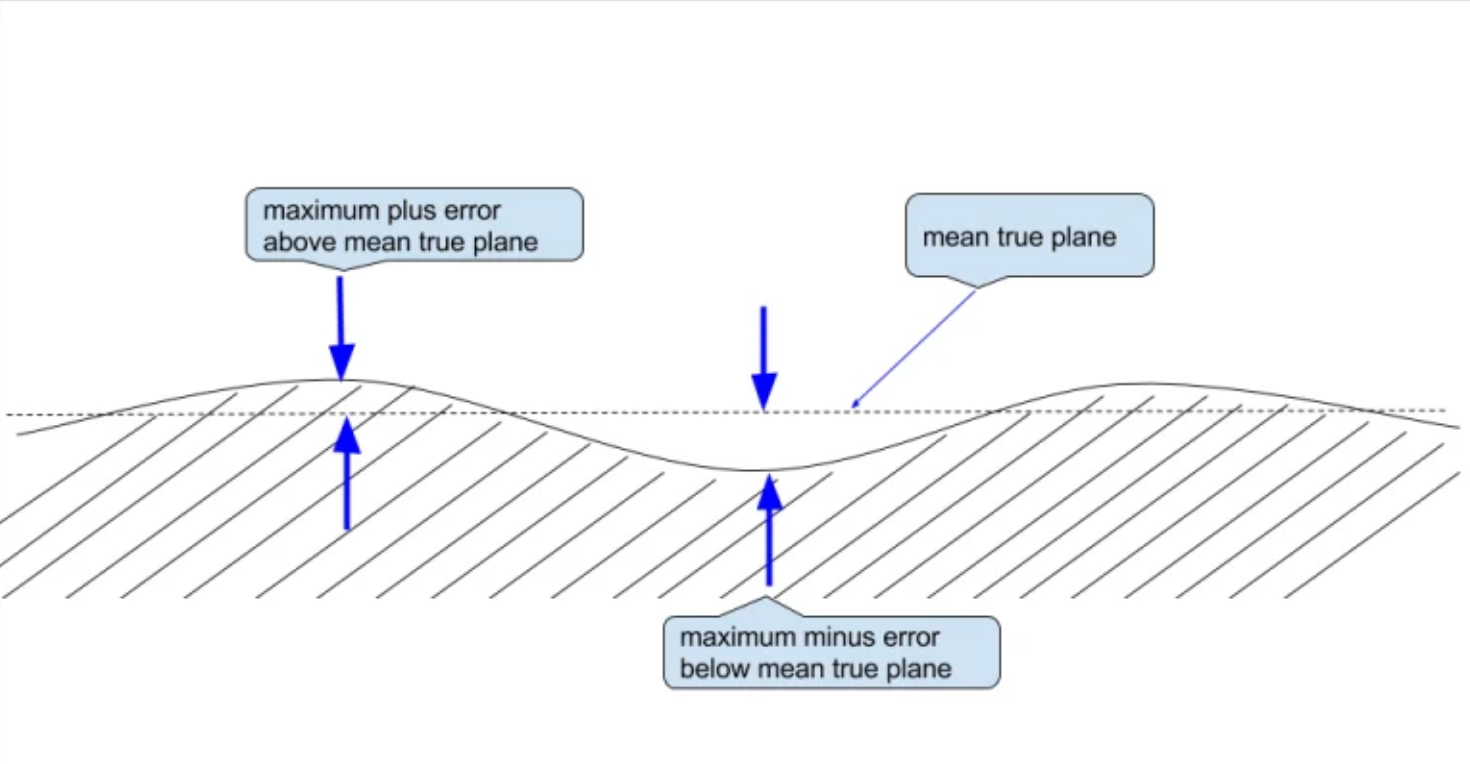

the departure of the highest and lowest points on the sole when measured relative to the mean true plane shall not exceed ±0.04mm

-- Section 8.1 Flatness of the sole (excluding corrugated soles)

I have reproduced the diagram from the standard that illustrates the point:

For now let us assume that the BS standard describes a level of flatness that is good enough for most woodwork . How can we test our planes against it?

Testing for flatness

First of all you will need a straight edge or a flat surface that has better tolerances than the standard. I have a 1ft steel rule made by Starrett and these are apparently guaranteed to be straight and parallel within 0.001″ (0.025mm) per foot. Thus if I can’t see any light between the straight edge and the sole, then the sole should be flatter than the standard.

The other way for testing flatness is to place the plane on a known flat surface and use a 0.04mm feeler gauge to try to get underneath the plane – if you can’t it is flatter than the standard. In the picture below I am using a piece of float glass:

Obviously these tests are only as good as your reference surfaces, but you get the idea.

Is a flatness tolerance of 0.04mm good enough?

… as you will read all over the internet, Lie Neilsen make the creme-de-la-creme of modern bench planes and according to universal consensus these planes will work “out of the box” without any fettling. Lie Neilsen says:

The soles of our planes are machine ground flat and square to .0015″ or better, regardless of length.

Lie Neilsen

.0015'' = 0.04mm, i.e the very same tolerance specified by the the engineers who created the BS standard all those years ago, so it looks like they knew what they were on about.

Does it really matter?

quite possibly not, however, it is not difficult to get Lie Neilsen levels of flatness with your el-cheapo ebay plane, and you can read the next thrilling instalment to find out how.

If you are in a hurry to get your old plane working you are just as well to skip this stage and go straight to sharpening your blade. The sharpening step obviously can’t be avoided and may well be enough on its own to get the plane working satisfactorily. You can always come back to the flattening step if you are not happy with the results.

You may also be interested to know that Japanese plane makers deliberately make their planes concave ensuring only that the areas at the toe, heel and immediately in front of the mouth are co-planer.

When you think about it, the fact that the three flat reference points bridge the hollows will mean that the plane will not rock around in use and that the spot immediately in front of the mouth still fulfils its purpose in compressing the wood fibres prior to cutting. Thus they avoid all the hassle of creating a completely flat sole and have the benefit of reduced friction, since there is a smaller surface area in contact with the wood.

If you are undeterred by these details and want to flatten your plane in any case, read on….

References

| 1⏎ | this is a metric version of the now withdrawn BS 3623:1963. There is also an ISO standard – 2726:1973 |