What is a firmer chisel?

Nowadays when we talk about firmer chisels we tend to think of a fairly stout chisel with parallel sides:

.. but in the past the term ‘firmer’ had a broader meaning, covering a wide range of general purpose chisels.

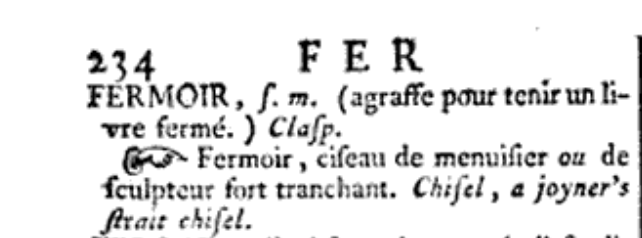

It is not clear why the term ‘firmer’ came to be used to refer to these chisels. The OED says it is an Anglicized form of the French word “formoir” (to form) and other dictionaries say it derives from the French work “fermoir” (clasp).

One of the earliest written accounts of woodworking in English is the Mechanick Exercises or the Doctrine of Handy-Work written by Joseph Moxon, first published as series of pamphlets in the late 1670s1). Moxon mentions four types of chisel: former, mortice, paring and ripping. On the “former” he says:

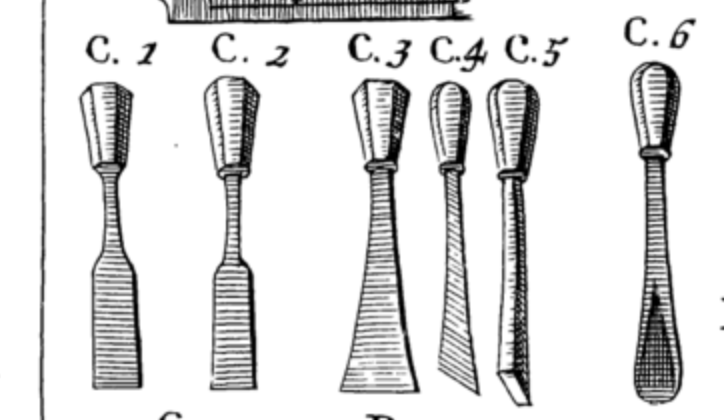

Formers marked C 1, C 3. are of several sizes. They are called Formers, because they are used before the paring chisels, even as the fore plane is used before the smoothing Plane…

The paring chisel marked C 2. must have a very fine and smooth edge. It’s Office is to follow the Former, and to pare off, and smoothes the Irregularities the Former made. It is not knockt upon with the Mallet…(instead) the top of the Helve (is) placed against the hollow of the inside of the right shoulder, with pressing the shoulder hard upon the Helve, the edge cuts and pares away the Irregularities

So for Moxon the former is used with a mallet to roughly chop out material and the paring chisel is pushed with the hand and shoulder to make fine paring cuts to clean up the job. Was the term “former” an old spelling, or could Moxon have simply got the name wrong?

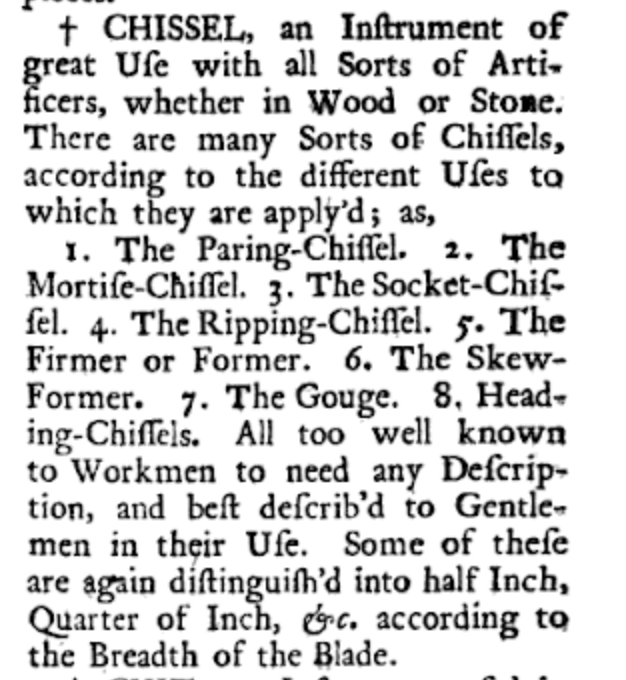

Some evidence that former is an older term that was eventually displaced by firmer can be found in Richard Neves’s 1736 Builder’s Dictionary which mentions a “Firmer or Former” chisel in a list of chisel types:

While Moxon was not a carpenter by trade and might conceivably have got the term wrong, particularly given the liassez faire attitude to spelling in the 18th century (both the extracts above are from the same edition of the dictionary!) such that Neve simply repeated the mistake, I think the more plausible explanation is that both former and firmer were used interchangeably in the C17th.

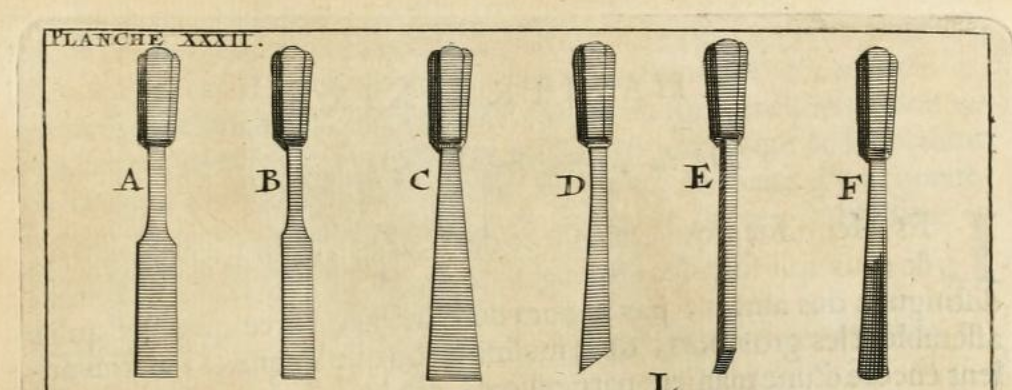

It is now generally accepted that many of the etchings in Moxon’s book were based on illustrations from an earlier French publication, André Félibien’s Des Principes de L’architecture (1676), and indeed this book shows a similar range of chisels:

Félibien’s descriptions do not exactly match Moxon’s, in particular, the first chisel is described as having two bevels whereas Moxon clearly describes it as having a single bevel(or “basil” to use his term), so it is reasonable to ask whether the illustrations of the french tools matched exactly their equivalents in England.

This French/English dictionary from 1756 translates Fermoir ciseau (chisel C above) as “joiners straight chisel”, which is rather unspecific perhaps suggesting a general purpose chisel:

Again, we can’t be entirely sure, but let’s give Moxon the benefit of the doubt and assume the illustration in his book is a fair representation of the tools actually in use in England at the time,

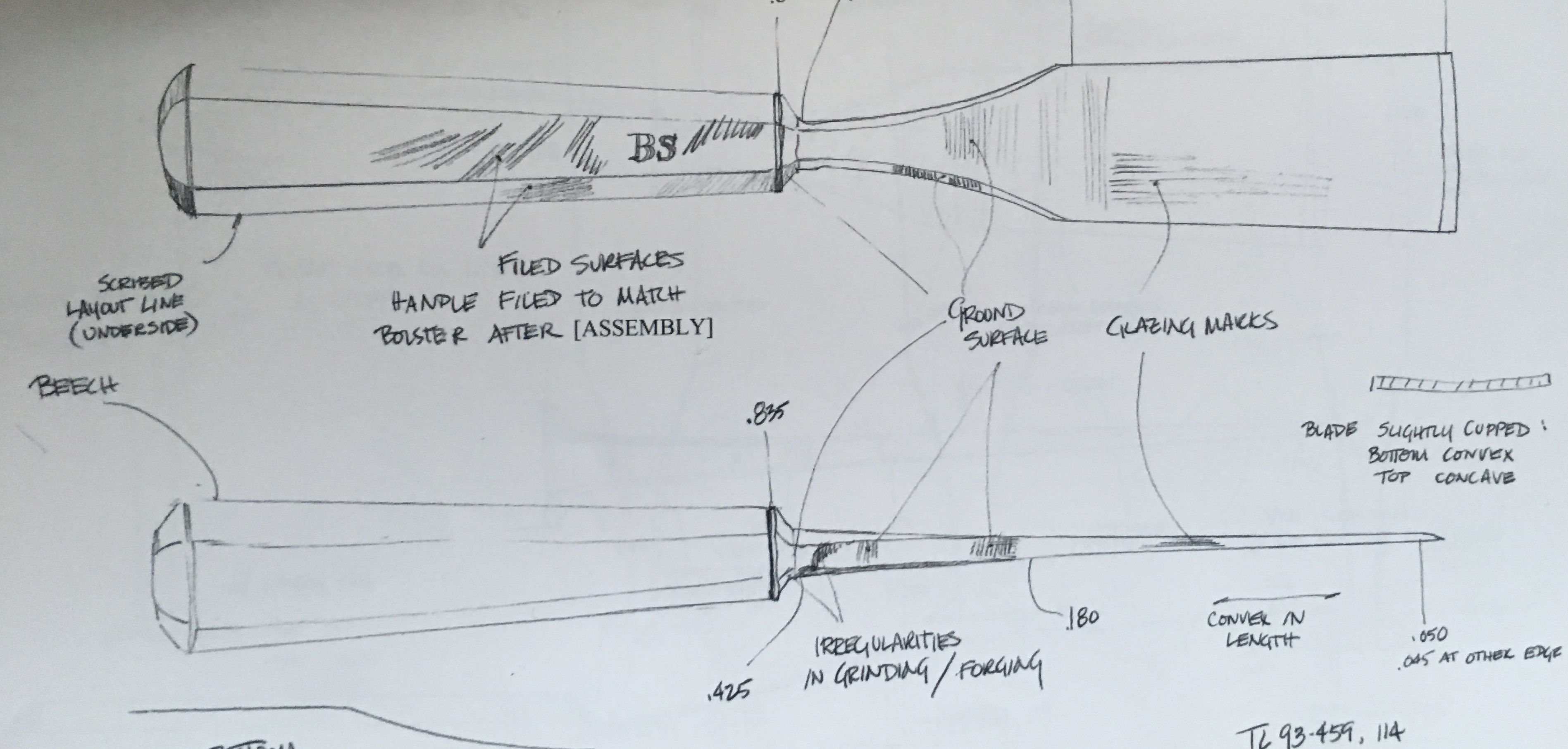

Certainly this style of chisel, where the body of the chisel is flared so it is wider at the tip than the shoulder, was in use in England 100 years later and we can see examples in the Seaton chest dating from the 1790s2), albeit the flair is rather less exaggerated than in the illustrations above. By the later part of the 19th century the sides of firmer chisels were more or less parallel (in practice, although they have apparently parallel sides, they are typically slightly tapered in two directions: they taper in thickness from bolster to tip, they also taper in width, widest at the tip. These two subtle features help prevent the chisel binding in the cut.).

One interesting feature of the firmer’s in Seaton’s chest is they are much thinner than the firmers we are used to today. No doubt this was convenient for fine work where tight access was required, for instance cleaning up the inside the tight corners of a dovetail joint, but the obvious disadvantage is that they are not as strong as they might otherwise be, making them vulnerable to damage when hit with a mallet. Indeed several of the Seaton chisels are broken: of the 48 chisels in the chest, there were 31 firmers and the rest were mortice chisels or heavier socket chisels both types designed for heavy duty work. The firmers consist of two very closely matched sets one made of solid cast steel and the other laminated. Perhaps he needed so many because they tended to break!.

So, in conclusion, a firmer/former is a chisel struck with a mallet and intended for quickly removing material.

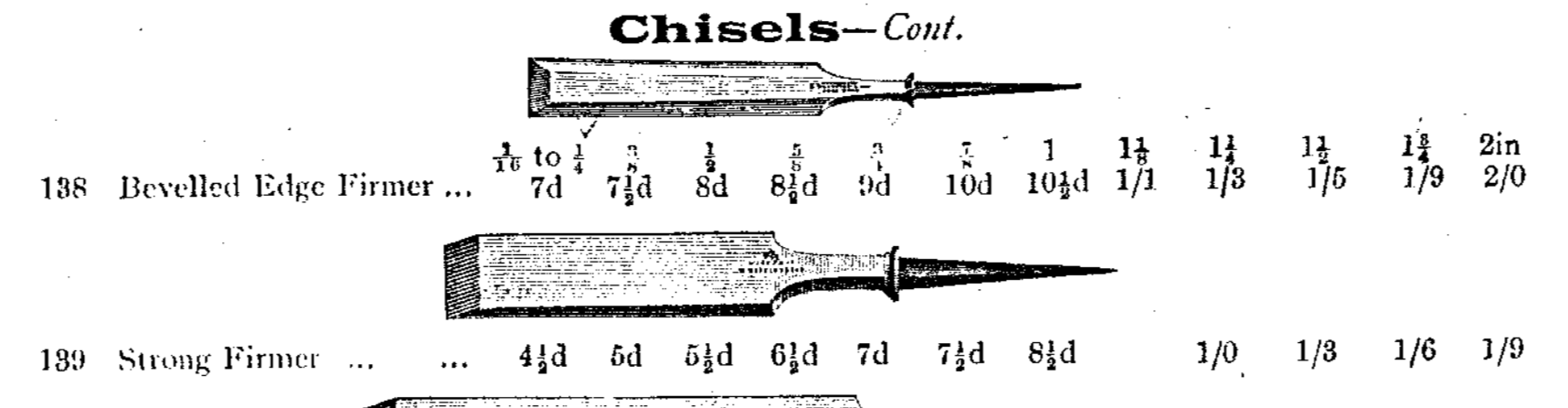

The bevelled edge firmer

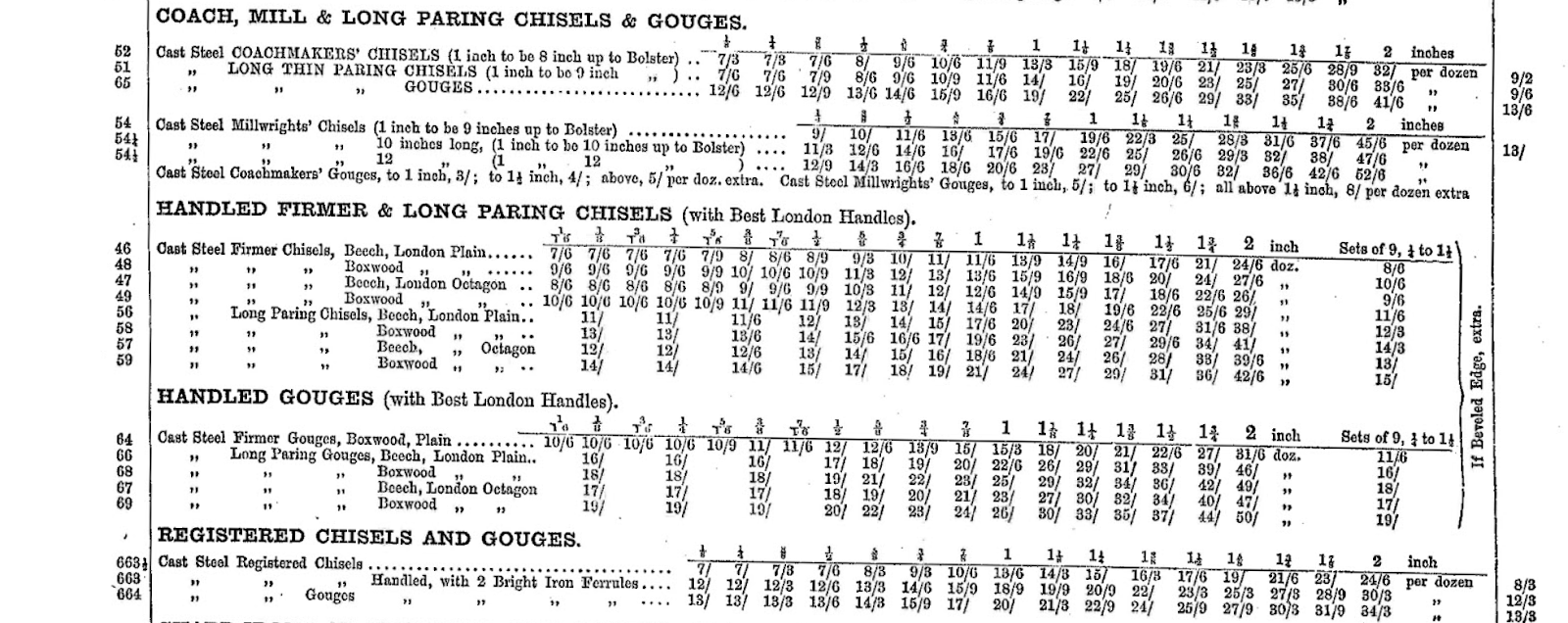

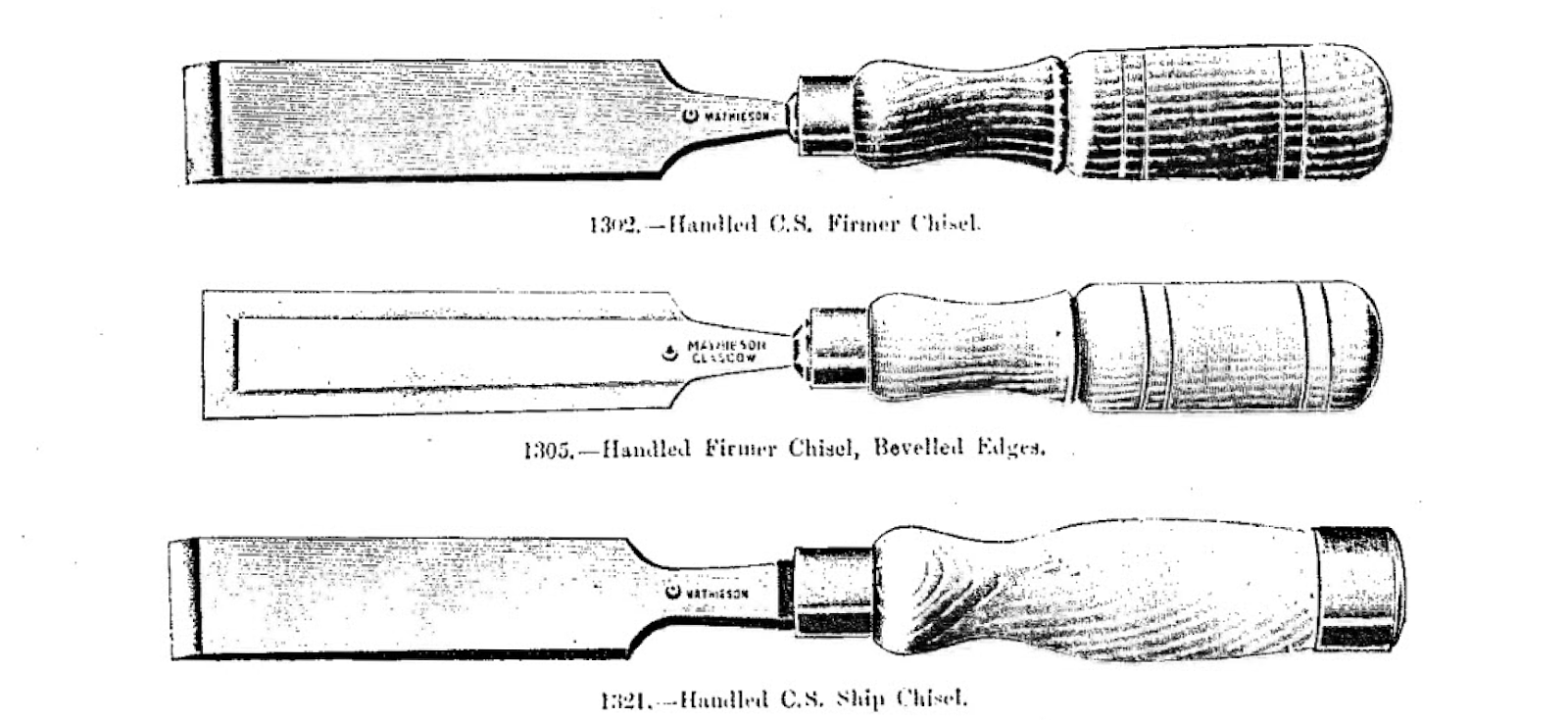

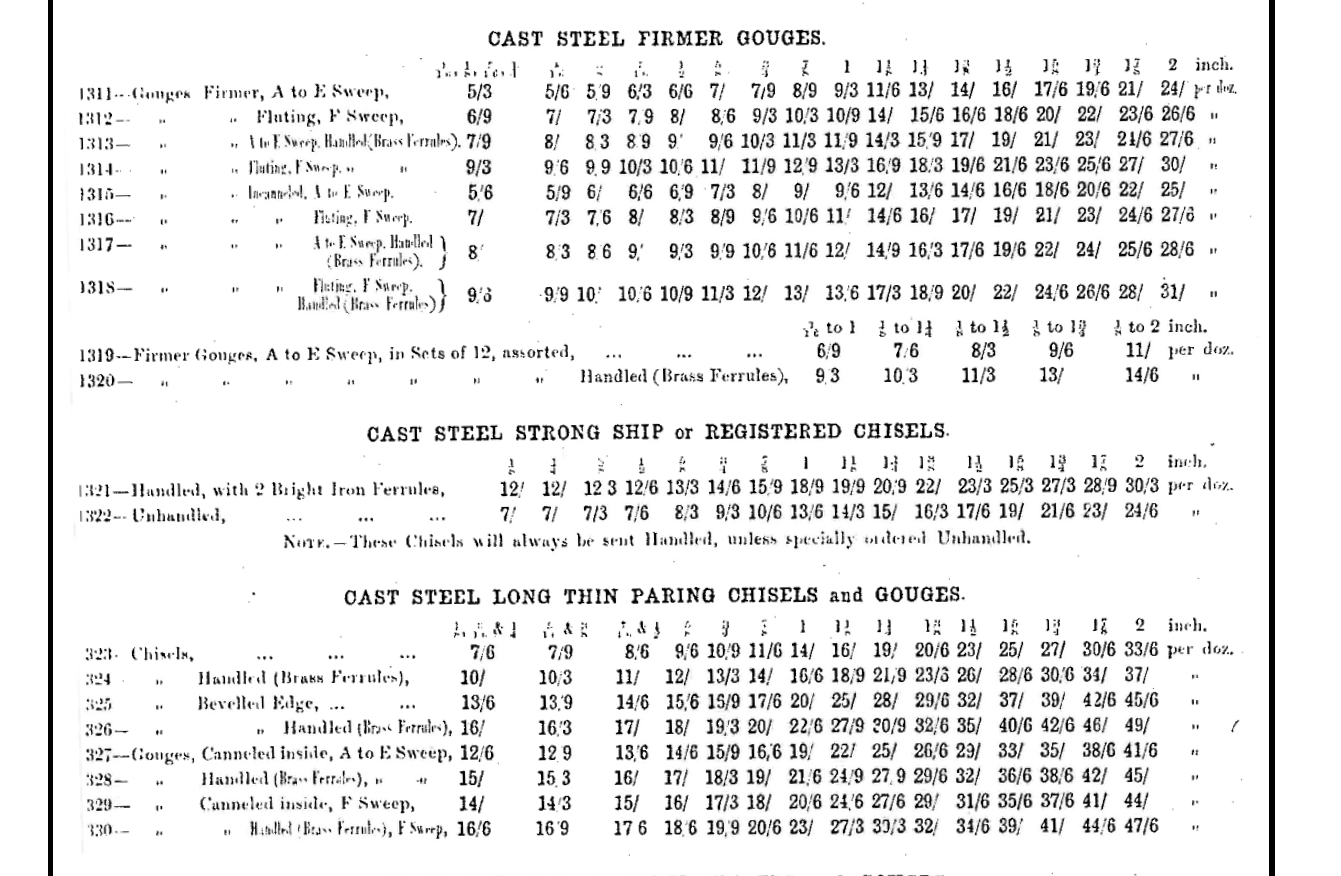

By the second half of the 19th century the bevel edge firmer was becoming popular in England. Although today we tend to think of this as a distinct type of chisel separate from firmers, in the 19th century they were simply another flavour of this general category:

This design is a good compromise between strength and utility: the narrow edges allow easy access into tight spots and the thicker section makes for a robust tool. However the design complicates manufacture – because there is additional grinding needed and heat treatment is more difficult because the different surface area on one side to the other changes the rate the metal cools and can cause the tool to warp when it is quenched – and this is reflected in the price.

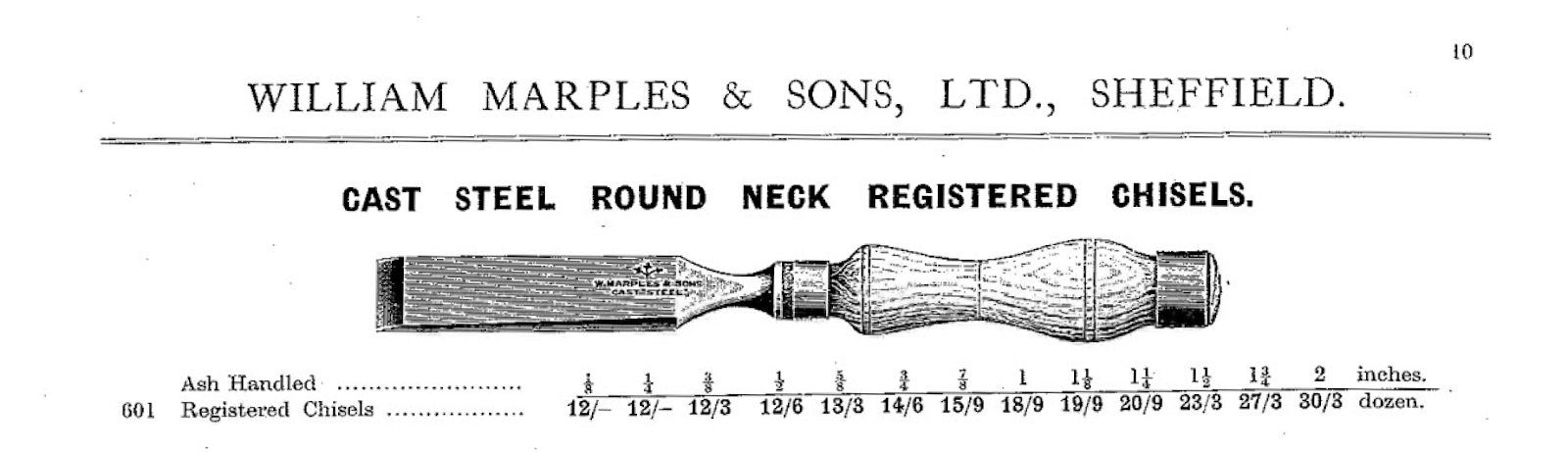

Registered Firmer

Another unusual term that has carried over from the C19th is registered firmer. A clue to their intended use is that they are generally only offered with a handle already attached, whereas other chisels are sold without handles so the user can add a one of their preferred shape. The reason appears to be that the handles for the registered chisels have been specially strengthened by the use of 2 ferrules:

Although the image above refers to a “Ship chisel” (suggesting rougher work on large timbers?) the subsequent price list refers to “strong ship or registered chisels” suggesting the terms were interchangeable:

So there you have it a “registered” chisel is a stout firmer chisel with an extra hoop that prevents splitting when struck with a metal hammer and with the optional addition of a shock absorbing leather washer. All these adaptions were intended to make it stand up to heavy work.

Why call them “registered”? I’m afraid I have not been able to find out. A commonly offered explanation is that it refers to a registered design patent taken out to cover this style, but I have not been able to substantiate that.

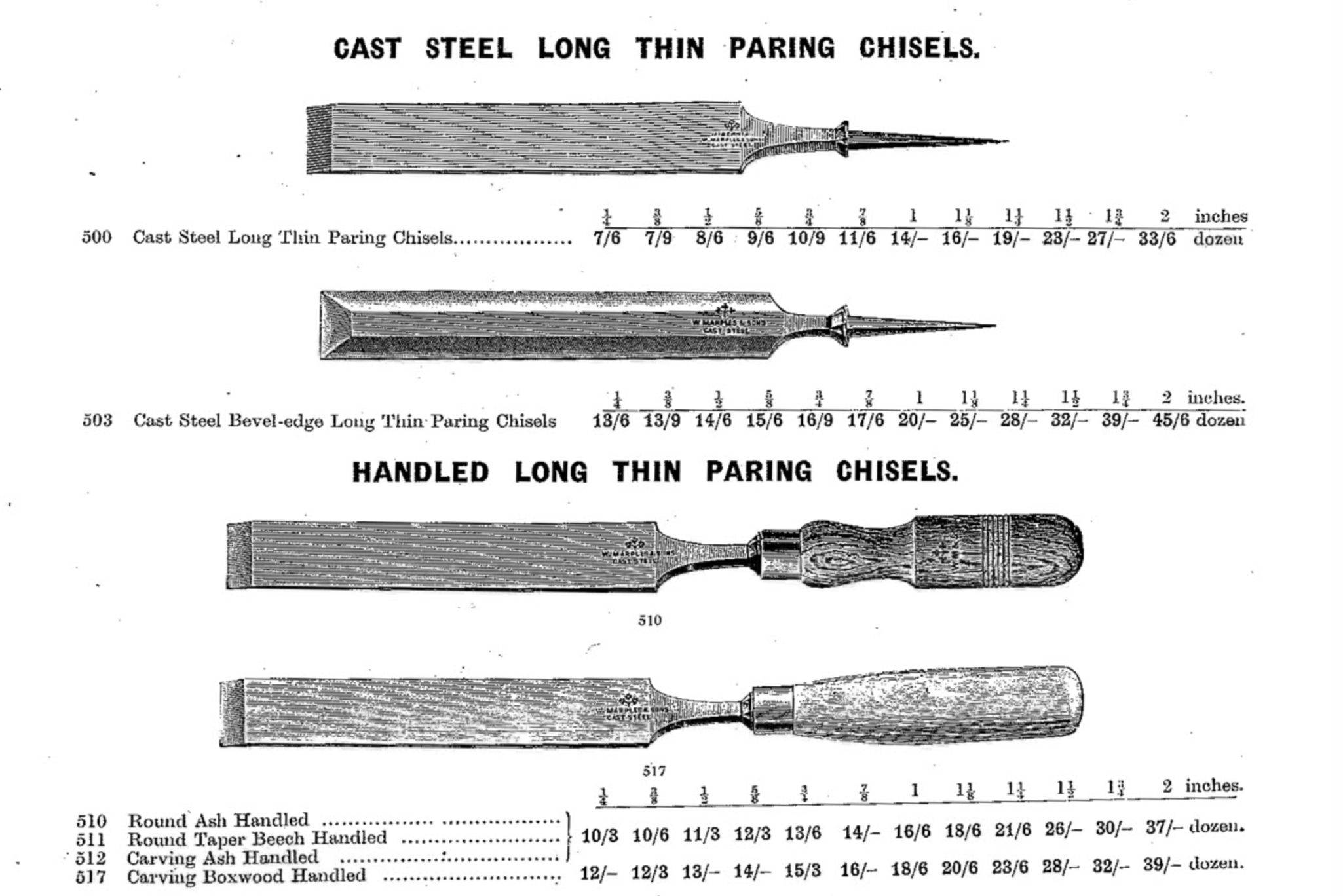

Paring Chisels

Paring chisels are long and thin:

As their name suggests these chisels are used for paring and, as Moxon explains, should not be struck with a mallet.

Although this is not obvious from the (presumably not to scale) illustration in Moxon’s book we can guess that the C17th versions must have been longer than average because of how he describes them being pushed with the shoulder, a process that would be rather awkward with a standard chisel. It is also convenient for fine work since, with a longer chisel, you can ‘sight’ down the length of the chisel and carefully control the cut.

The additional length also helps ‘steer’ the chisel giving more control for finer work, while their thin profile allows the blade to flex so that the depth of the cut can be adjusted by pushing down on the blade or using the handle as a lever to control pressure at the cutting edge.

From the 2nd half of the C19th they were available with parallel or bevel edges, with the latter being more expensive.

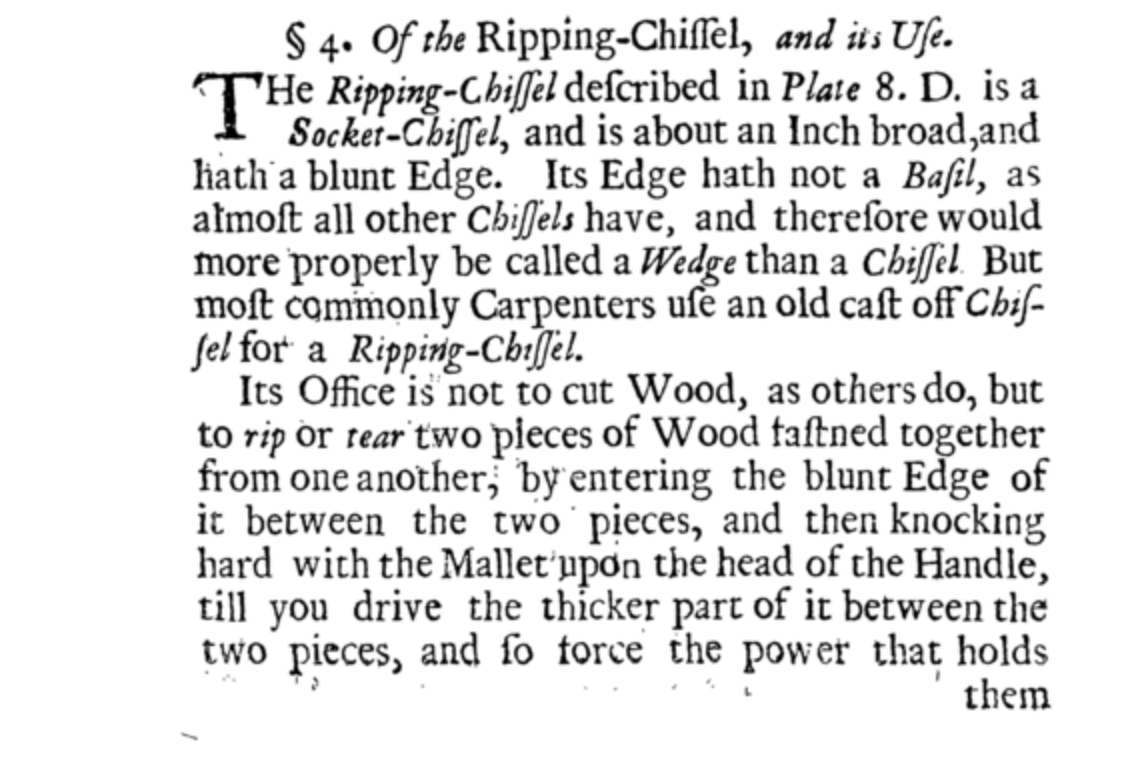

Ripping Chisel

The term ripping chisel has fallen out of common use, but according to Peter Nicholson is defined as follows:

.. and Moxon:

so a ripping chisel is an old chisel used for rough work or as a wedge for separating planks of wood that have been nailed together.

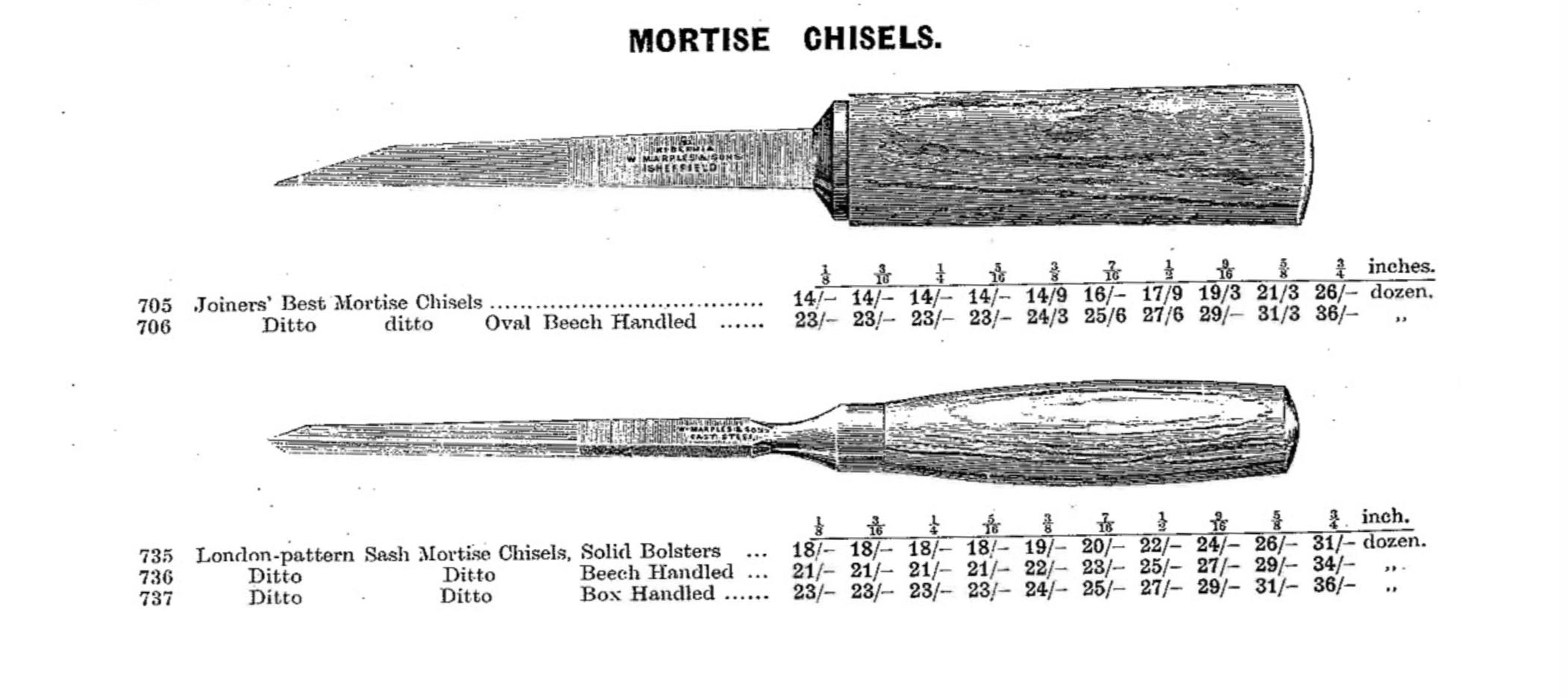

Mortise Chisels

Another very old design, mortice chisels have a distinctive trapezoid cross section and are very strong, being designed to be hit hard when creating a mortice. In recent times in America these chisels have been given the amusing nickname ‘pig sticker’, for obvious reasons.

Another version, called the sash mortise – after the sash window making trade – is lighter and suited to the softwoods typically used in house joinery:

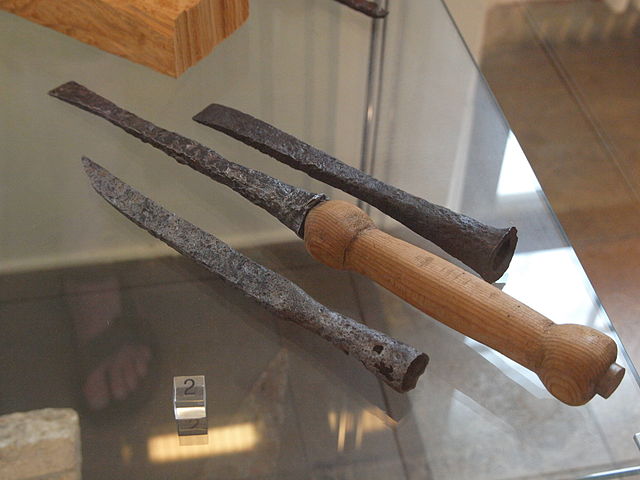

The design is very old and Roman examples over 2000 years old have been found:

The chisel nearest the bottom of the picture is the mortise chisel. This example has a socket to receive the wooden handle (now lost), but the Romans also made tang chisels (the middle chisel above is an example and has a replacement handle).

That’s quite enough old chisels. In the next post, a bit about a (relatively) modern chisel – the Ward & Payne Aristocrat.

| 1 | the complete third version published in 1703 can be found here |

|---|---|

| 2 | this chest of tools was put together by Benjamin Seaton – they were hardly used and have survived pretty much intact |